Equifax’s shareholders want details about the company’s attempts to get its foot in the door with politicians

Following the massive data breach last fall at Equifax that exposed the personal data of as many as 147 million Americans, Equifax’s consumers affected by the breach are still recovering from having their personal information exposed to identity thieves. As the company holds its first annual shareholder meeting since the breach, all eyes are on how the company will clean up its act and be more accountable to its investors and the public. One arena where the company refuses to be held accountable is disclosing its political spending, which is why shareholders have filed a resolution asking for more details about how the company attempts to influence elections.

In 2017, Equifax spent more than $1 million lobbying the federal government, and while it’s important to track a company’s lobbying activity to determine how it may be attempting to directly influence politicians, lobbying is only one side of the influence coin. The other side is election spending, which is often used as a foot in the door for companies or special interests looking to curry favor with a politician. By supporting a candidate’s run for office wealthy special interests are more likely to build a relationship that leads to better lobbying access down the road.

Just last week, Mick Mulvaney, who was formerly a member of Congress and who is now head of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and acting director of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), illustrated this pay- to- play dynamic in American politics. Mulvaney said to a room full of attendees at the American Bankers Association conference what America knows in its gut, but that politicians have been careful to avoid admitting directly: “If you’re a lobbyist who never gave us money I didn’t talk to you. If you’re a lobbyist who gave us money I might talk to you.”

Given these remarks indicating that access to Mulvaney’s office was essentially for sale, and the hot water that Equifax is in, it’s important to note thatEquifax had previously donated to Mulvaney’s campaign for Congress. Since ascending to the role of CFPB acting director, the former South Carolina Congressman has been attempting to dismantle the protections put in place for consumers when the agency was created in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crash. One resource that Mulvaney has been particularly keen on eliminating is the consumer complaint database, which tallies how many complaints have come in on a particular financial company. The company with the most complaints in this database is Equifax.

While many of the complaints have come in since the data breach, Equifax has been lobbying on the database since 2014. In that year, the CFPB proposed publishing the consumer narratives that correspond with the complaints and Equifax began lobbying against that proposal. In 2016, while still in Congress, Representative Mulvaney introduced a bill that would restrict the CFBP’s efforts to make the consumer complaint narratives public. That year, records show that Equifax lobbied the CFPB on the database and the U.S. House of Representatives on Mulvaney’s bill (of which he was the sole sponsor). Since Mulvaney left Congress and took up his duel posts at the CFPB and OMB, Equifax has lobbied both agencies.

One could dismiss the story of Equifax and Mulvaney as one of circumstantial evidence, but the story of corruption in America is not typically one of direct bribes, but one of webs of influence spun between companies, trade associations, and their lobbyists where financial links are hard to trace and conversations impossible to prove. What is sure is that corporate executives are getting what they want out of the process- higher profits and less accountability.

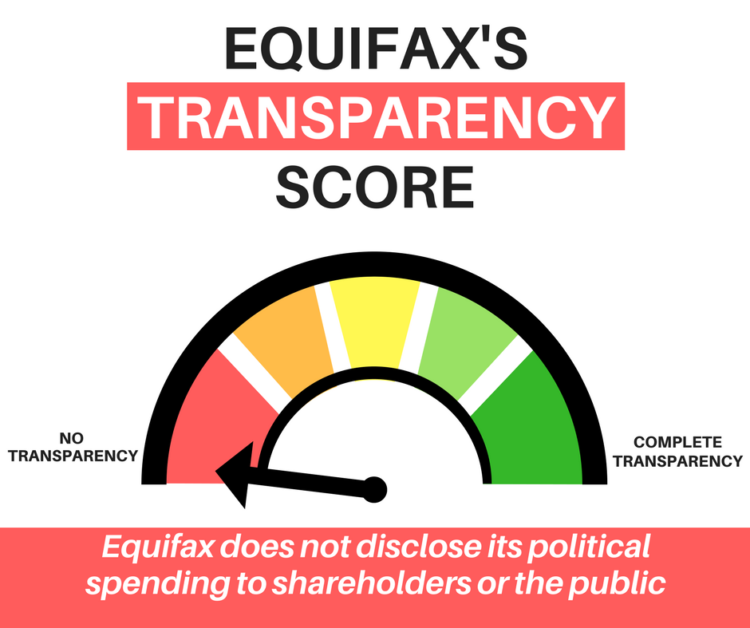

Given the power that election spending has to get your foot in the door with elected officials, it’s an affront to our democracy that a lot of election spending is secret. Because of the lobbying disclosure laws that are already on the books we have some picture of how companies attempt to influence policy, but election spending can be much harder to track, especially when it goes through secretive conduits like the trade associations or politically active nonprofits. Companies and special interests can donate to trade associations or politically active nonprofits that spend money to influence elections and those donations do not need to be disclosed. Equifax in particular claims that it fully discloses, but will not share whether it makes payments to trade associations or politically active nonprofits to influence elections on the company’s behalf. It’s time for the company to take responsibility and support shareholders calling for increased transparency and accountability. If you are a shareholder in Equifax, take action and vote in favor of the political spending disclosure proposal. If you’re a consumer, it’s critically important to raise your voice and call on Equifax to be transparent. Even more importantly, in order for American democracy to survive, the cycle of secret influence and pay- to- play politics must come to an end.

Learn more about Mick Mulvaney and the companies at the top of the CFPB consumer complaint database from coalition partner, Public Citizen. Read the full report here.